The silent you

You are more than you think you are - and you know more than you can ever articulate.

“I think, therefore I am” - said a guy in the 17th century, and it took the world by storm, becoming the very foundation of modern science and knowledge. A lot could be said about that. For now, let’s just say that we’re living four centuries later. And in that time, modern sciences, with methods built on those very Cartesian ideas, came to a conclusion that this slogan is a gross simplification - and therefore, mostly wrong.

If you wanted something that reflects the reality a bit more accurately, you could say: I think - therefore I am a highly developed nervous system that is capable of formulating abstract concepts. Or, better said: there is a highly developed nervous system that is capable of producing concepts. One of these concepts is ‘I am’ - an expression of my sense of self.

But that sense of self exists beyond conscious thought, and it exists because there’s a body that is capable of producing it. The feeling of ‘I am’ - because it is more than just a thought - somehow emerges from a complex system of cells that organizes itself around communication through electrical and chemical impulses. For simplification, the thinking calls this system “me”.

I know, doesn’t have the same ring to it.

But maybe the fans of Descartes should have listened to other philosophical ancestors: to err is human, but to persist in error is diabolical…1

It’s been almost 30 years since neuroscientist António Damasio wrote about the “Descartes’ Error” and the mistake of putting rational thought on the pedestal, far away from our flesh. Since then, a vast array of research has confirmed it over and over again: Body and mind are not separate, and rational thought cannot exist without sensory perception and emotions.

As to the “I am” part: with Anil Seth (another neuroscientist),2 anything that arises in consciousness is a perceptual prediction, something he calls a controlled hallucination, experienced with, through, and because of our living body. That body constructs the perception of the world around you, and it constructs you, for the single purpose of keeping you alive.

“You”, as in: that very body you identify with and experience the world through.

So it’s not: I think, therefore I am.

But rather: The living matter which I embody makes me feel that I am.

…

Is your conscious brain boiling already?

Good.

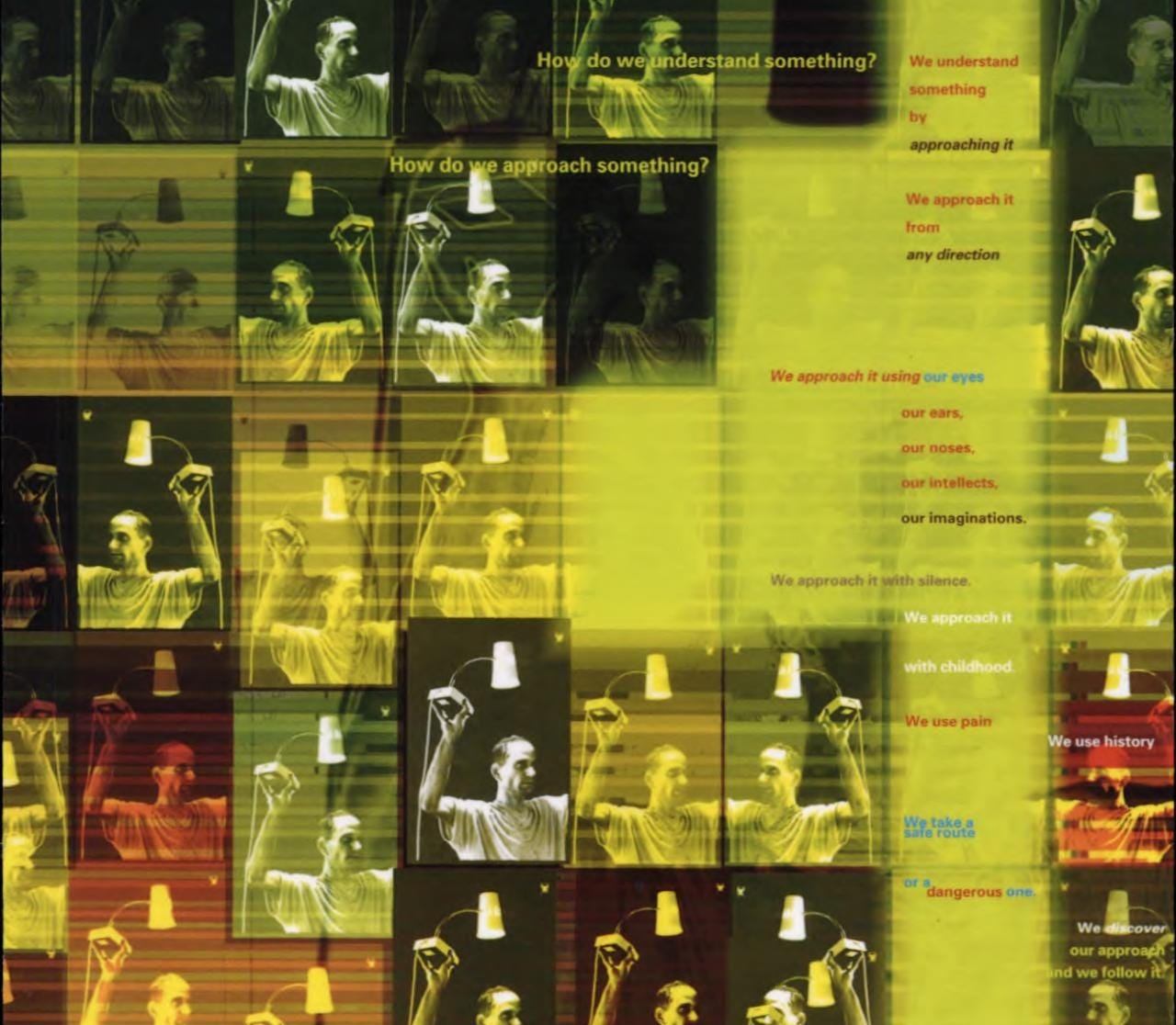

I want to throw you off balance. You need to be off balance to be able to peer on things that live beyond the world of rational thinking without bias.

I’ve said it, I’ll say it again, because it’s important: I don’t aim at rejecting rationality. BUT, if you really look at it, rational angle is really unhelpful in trying to understand things that aren’t linear, logical, linguistic. And, spoiler alert: a lot of things aren’t. A big part of you isn’t either. So, Socrates was right on the money when he said “I know that I know nothing”.3

At the same time, beneath the facts, concepts and figures we remember on the conscious, rational level, there lies a deep warm lake of unconscious soup. And, although many would disagree, that soup is also knowledge - knowledge we use everyday in our decisions and actions, even if we don’t really register its existence. You might think of yourself as the master of your fate, but, in fact, science shows us that your decisions usually rely more on emotional response than the rational one. Moreover, it is only a small part of your overall decision-making-process: in most cases, the body makes the decision before you consciously arrive at it.4 There isn’t time to wait for the conscious you. Survival often requires a millisecond reaction to the environment.

Okay, but what about that soup of knowledge?

Tacit knowing5 is the formal name for the soup. The term was coined by Michael Polanyi.6 He was also the one to suggest the verb-form of “knowing” - because what goes on in the soup cannot really be put in any static, clearly identifiable shape or form. Tacit knowing is a broad knowing we possess without being able to convey it in words. It’s silent. Some call the deeper aspects of it “dark”. It lives in our bodies, and it defies expressing in words and concepts. It’s how you walk, move, and how you know your way around social cues; it’s the way you routinely use tools or approach solving complex problems; the way you play music without really thinking. Your gut feeling about situations. Instinct. Insight. Intuition... It’s how we make sense of the world, and is learned through being in and with the world.7

So you do know more than you think. The thing is, it’s covered in deep dark fog, and the only way to get touch with it is through the body - going deep into that fog.

Tacit knowing, despite being silent, is also the absolute foundation of language communication: it is rooted in experience, and that is where the meaning behind our words and concepts arises from.

“Love”. “Loss”.

“Blue”.

Maurice Merlau-Ponty, a really interesting philosopher dealing with perception and experience, put it this way: “My body has its world, understand its world, without having to make use of my ‘symbolic’ or ‘objectifying’ function”.8 Just think about the perception of colours: a newborn can see the blue of a clear sky, despite not knowing that the sky is blue. They don’t know what the sky is and what “blue” means. And I think that in that moment, before they learn that “that’s the sky” and that it’s blue, the sky shows itself to them with a mystery and magic that no word can capture. Later, we call it “blue” and we might even connect it to that first experience of an open sky. But does the word “blue” really convey it?

Does “I am” express what you feel, being alive?

The best known example for the way tacit knowing functions is our ability to recognize faces: we remember and recognize faces of people we know well and interact with often - but we can also tell apart those we only met once or twice, or seen only in photographs. But if I asked you to describe in detail the face of a co-worker you see on a daily basis - or even a member of your family - you might have to think for a minute. And if I drew a memory sketch based on your description, it probably wouldn’t be very accurate, and you could see it plain as day, without being able to tell me what exactly is wrong with that portrait.

And that’s how tacit knowing works: in big picture terms. We recognize the unique constellation of elements, we don’t analyse the components on their own.

Tacit knowing is not nitpicking. We’re able to interact with complexity, because we don’t lose time on details. Polanyi calls it emergence: the whole is always more than just the sum of parts. If you had to think about each tiny process involved in the action of walking, you’d never move from your spot.

And that’s why the sentence “I am” is just a weak representation of your feeling of existence. To be alive is complex, multilayered, paradoxical, fabulously abundant. Too rich for words. Somehow, too rich for knowing as well.

Tacit knowing is the wordless, practical, experiential grasp of what is going in around you and in you. And this comprises a bigger part of you than all the things you can think.

So why do we live in the world of words?

Well, you can blame Descartes, but the dogmatic, almost religious strength of his words has little to do with the guy himself - after all, he’s been dead for a long time. I think it’s rather about the deeply rooted fear of letting ourselves fully experience what we experience. To let go of our obsession of concepts means to really get acquainted with the tacit soup of the ineffable. It means to dive deep into the feelings and somatic experiences behind our words and actions.

And to feel that is to lose control.

In the most messy way possible, because you find yourself at a point in which you have difficulty expressing, communicating and explaining to others what you experience in the newly discovered “silent you”.

But it’s still completely worth it. Because we do get to know on a deeper, emergent level. We get to understand things we struggle with otherwise. It doesn’t happen overnight, but it is possible to train ourselves in getting intimate with the depths of silent knowing within us.

It is a paradox and a kind of hopeless mission that I am writing about all that.

I do it anyway, because, firstly, I’m not merely interested in getting to know my soma - I am also interested in inviting others into the depths of their soma. Not only because I think it’s good for you on an individual level, but also because I am convinced it makes us better researchers, teachers, managers, artists, practitioners - better people, no matter what you do in your life.

In the end, the way towards it is yours, and yours alone.

Secondly, I write notwithstanding the seeming pointlessness, because finding your way into the depths of experience is one thing, but finding your way back and communicating with others about it is another. I have spent a lot of time working with different ways of translating our tacit experiences into communicable forms. And I think it can do some good to explore these further, in this experimental space of translating my translations. And so, words will be my crutches, as we go into some riskier translatory forms.

But more on that next time I get the sudden urge to write.

Nudges and signposts for today

One of my favourite talks by Reggie Ray (Dharma Ocean), because it awakes a longing in me I can only quench by going deeper: This neurobiologically-informed invitation to get in touch with the “dark knowledge” of the tacit dimension - great talk on knowing, perception, and the heart from a point of view of a somatic work/meditation practice lineage.

“My Stroke of Insight” by Jill Bolte Taylor - it’s an older book, not state-of-the-art science, but a fascinating, eye-opening and very valuable personal account of a neurobiologist that experience a stroke - and what she learned from that about perception, identity, and being.

My recently published chapter on using arts and dance to let go of control for better research.

And don’t forget the links in the footnotes below!

I really love Brian Cox’s approach on that matter.

There is A LOT going on in contemporary neuroscience, and it’s absolutely fascinating - even if many of these things remain on a level of scientifically funded theory, something that research suggests but cannot yet prove. Anil Seth wrote a whole book on “Being You” - here is a podcast-summary of the book in the words of the author.

This statement is always a great reminder and talking about it could fill another essay. We do know shit. And it’s a kind of paradox I go on to talk about knowing. But a text is a linear form, and linear forms have limitations when it comes to holding paradoxes. My friend wrote a great essay on knowing shit about the world, which is still very relevant to what I am talking about here - you can read it on his blog.

A lot of research going on here as well - see for example: “New Insights into the Neuroscience Behind Conscious Awareness of Choice” by CalTech, or “Our brains reveal our choices before we’re even aware of them” from UNSW Sidney.

From Latin tacitus: “passt over in silence, done without words, assumed as a matter of course, silent”.

Michael Polanyi was a my-kind-of-person - a polymath dabbling in chemistry, economy, and philosophy. I think many polymaths have an instinctive understanding of the tacit dimension - multidisciplinarity requires it. Polanyi’s book, “The Tacit Dimension”, was published originally in 1966.

A big clue as to why AI has difficulty learning complex tasks.

In “Phenomenology of Perception”, originally published in 1945. If you don’t feel like reading Merlau-Ponty in his own words, be sure to check out the amazingly written “The Spell of the Sensuous” by David Abram - he offers a good intro to Merlau-Ponty’s phenomenology in the few first chapters and builds on that to offer a great analysis of how inventing written language changed our perception of the world - one of my favourite books around my topics.